In Chicago an extremely mild winter has given way to an early spring that feels like June. For 15 of the last 16 days we’ve had highs above 60 degrees. Today was the 8th day in a row to see a high of 80 degrees (The average for this time of year is about 50 degrees).

Last weekend the City celebrated St. Patrick’s Day by spilling out of its dark taverns into sun-baked sidewalks, beer gardens and sandy beaches. Last night, as I ran near Montrose Beach, the surrounding park was already alive with the sound friends playing soccer and the smells of barbeque on the grill.

Obviously we can't point to a single event or a season as evidence of climate change, but the trend is certainly warming. Since we can't distinguish an average increase of 2 degrees over the course of our lifetime, the potential impacts of climate change only become tangible after extreme events. A winter and a spring this warm may not happen again for decades, but as long as the average continues to increase, things will change.

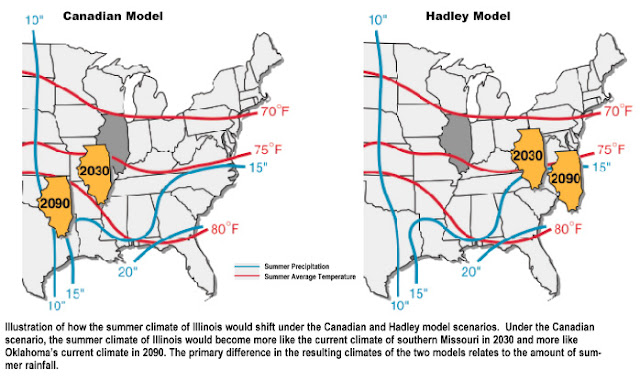

Chicago is already beginning to consider the implications of a warmer future. Depending on the model used to project weather scenarios, our climate may resemble contemporary St. Louis or Pittsburgh by 2030 and Oklahoma City or Washington D.C. by 2090 (US Global Change Research Program). In light of this possibility Chicago has started implementing a Climate Action Plan that, among other things, directs the parks department to plant trees that are native to southern climates. Kudzu, for example – a fast growing, parasitic plant that blankets parts of the Deep South - has already made its way to Southern Illinois.

Climate change is likely to have an untold number of consequences for Chicago and the Great Lakes region within the next century. Agricultural production and the health of the region’s watersheds are undoubtedly the most important concerns going forward. Though many models predict increased rainfall for the Midwest, more of our precipitation may fall as intense storms that cause increased flooding and soil erosion and generally harm agriculture. Warmer temperatures are also likely to affect plant and soil health. Warmer weather might allow for extended growing seasons and more diverse agricultural production or it may trigger crop increased crop failures.

With 20% of the World’s freshwater the Great Lakes are increasingly recognized as an absolutely vital yet increasingly fragile natural resource. Decreasing ice cover during the winter and hotter temperatures in the summer will undoubtedly increase evaporation across the region. This year saw almost no ice cover in Lake Michigan and very little in Lake Superior. The marine layer of fog that Chicago often experiences in spring (much earlier than usual this year) is largely the result of this evaporation. Though the water levels of the lakes fluctuate from year to year they certainly aren’t immune to the effects of climate change or other man-made diversions. Lower, warmer lake levels will not only reduce the quantity of this vital freshwater resource, they may dramatically impact shipping and recreation, not to mention the aquatic life of the lakes themselves.

|

| Change in Water Volume of the Aral Sea (1989 - 2008) |

The Aral Sea of Central Asia is a dramatic case study for how such a large body of water can almost completely disappear in a matter of decades. Though the depletion of the Aral Sea was largely caused by the diversion of its tributary rivers for irrigation, it should nevertheless serve as a sober warning to the future of the Great Lakes - especially any further attempt to divert water for consumption and agriculture. Recognizing the fragility of the Great Lakes, surrounding states and Canadian provinces are increasingly coming together to manage and protect this resource through a series of charters and binding compacts.

Most of the controversy over the future health of the Great Lakes has been centered on Chicago’s backwards-flowing river and the city’s continued subsidization of suburban water consumption. Chicago became an important outpost 175 years ago by occupying a narrow portage between the Great Lakes and the Mississippi Watersheds. The construction of a ship canal connecting these watersheds facilitated the transportation of goods from Chicago to the Eastern Seaboard and the Gulf Coast. Later the reversal of the river for sanitation purposes opened a small plug in the bottom of Lake Michigan. To this day, every time the locks open, millions of gallons of fresh water are released from the lakes into the Gulf of Mexico. Though the locks are now tightly regulated, environmental groups are increasingly campaigning for a restoration of the river’s course back into Lake Michigan.

The Great Lakes Watershed essentially ends at Chicago's western border, near Harlem Avenue. Though the western suburbs are almost entirely located within the Mississippi Watershed they have historically tapped into the City’s water supply from Lake Michigan. Currently suburbs as far as 40 miles away from the Lake are receiving its water. More recently, Mayor Rahm Emanuel has proposed doubling water rates for suburban users as a way to raise revenue for system upgrades. There’s no doubt that controversy will continue to surround suburban access to lake water and that this may become an increasingly important leveraging arm for the City of Chicago. It may also create further divisions among an already polarized region.

Despite the challenges we’ll face in the future, Chicago’s connection to the Great Lakes and the rich farm land of the Midwest will likely make it one of the most resilient major cities in the World. With strategic transit and infrastructure improvements the City and its older suburbs are capable of absorbing literally millions of people. Indeed, the former Rust Belt, a semi-abandoned and underutilized network of towns and cities from Milwaukee to Buffalo, may ultimately prove to be the most resilient and vital region of North America.

Coastal cities are likely to face a number of challenges related to rising sea levels. While places like New York and Boston erect protective sea barriers like those currently deployed in the Netherlands, neighborhoods like Lower Manhattan and the Back Bay may become so vulnerable to flooding that they’re prohibitively expensive to insure. The threat of rising seas will almost certainly have devastating affects on much flatter Gulf Coast cities like New Orleans and Miami (Surging Seas, an interactive rising sea level map).

Much of the West and South will likely be threatened by extreme heat, drought, water scarcity and increased risk to wildfires. Dallas experienced a record 70 days of 100 degree heat last summer. The hottest summer on record and the historic drought across the Southwest cost the Texas agricultural industry $8 billion last year alone. If the neighboring Ogallala Aquifer is depleted a huge portion of the High Plaines will risk almost certain desertification. As glaciers and snow melt decrease desertification may also creep into the central valley of California, the nations most diverse agricultural region.

|

| Western Forest devastated by the Pine Beetle |

In the Rocky Mountains longer periods of warmth have likely increased the breeding cycle of pine beetles that are now devastating millions of acres of forestland from Colorado to British Columbia. Of course, it goes without saying that climate change and decreased snow pack will threaten the entire recreation industry of the Mountain West, not to mention its natural beauty.

Almost every major city from Los Angeles to Atlanta is already facing serious water shortages that will certainly become more debilitating as the climate warms. Most of these cities are also characterized by extreme decentralization, low-density suburban sprawl and complete auto-dependency. Indeed, almost every city and suburb that we built since World War II is highly dependent on the subsidization of gas, highways, housing and water. Our nation pursued these subsidies as federal policies of growth and dispersion. In many ways we built our economy on around the consumer societ that it created. These policies and sunny suburban dreams were incredibly appealing to a nation with a long mythology of the frontier and an ethic of rugged individualism. Unfortunately that dream maybe over now.

All of this, of course, remains highly speculative. Cities like Los Angeles and Atlanta are unlikely to disappear any time soon. However, if the predictions of the climate models are reasonably accurate, most cities of the Sunbelt may be compelled to shrink to a size that is reasonably sustainable within their region. It may take decades for the consequences of climate change to begin noticeably affecting some places. It might not even happen within our lifetime. It might never happen. Technology might save us! Then again, it might not. It doesn’t hurt to consider alternative possibilities. It doesn’t hurt to begin looking for the most prudent opportunities of the future.

No comments:

Post a Comment